Dante’s Inferno is far more popular than Paradise. What does that say about us?

Dante Alighieri’s Divine Comedy is a monumental work in the canon of European literature and a cornerstone of world literature. In it, a semi-fictionalized version of the author describes an epic journey that took him through all three stages of the Christian (well, Catholic) afterlife, starting with hell, followed by purgatory, and ending with paradise.

Of these three sections — also referred to as “cantica” — the first, Inferno, is by far the most beloved. It has received the most attention from scholars and casual readers alike. It has been adapted into numerous plays and movies. It was even used as the foundation for a 2010 video game, which turned Dante from a poet into a crusader out to save his beloved Beatrice from the claws of Lucifer himself.

Purgatorio and Paradiso have, by contrast, received less adoration. Not because they are inferior in quality — both contain some of Dante’s finest lines — but because they have struggled to compete with the inherent marketability of Inferno. Indeed, the first (and most read) cantica of Dante’s Comedy is not only the most visually striking but also the most easily digestible of the poem.

“One finds few who will claim (or admit) that it is their favorite cantica.” That’s what Robert Hollander, the late professor of European literature, had to say about Paradiso in the introduction to his 2007 English translation of the Comedy. Understanding why this is the case not only will help us better understand the poem itself but our own attraction to it as well.

Dante: mapping out the afterlife

The further Dante ventures into the afterlife, the less compelling his journey becomes. That’s how many readers feel, and to a certain extent, it is easy to see why. The Inferno provides, as mentioned, a striking setting. In a stroke of literary genius, Dante divided hell into nine separate circles, with each circle punishing a particular group of sinners.

Over the course of 104 chapters, Dante describes a variety of locations, each of which is completely different from the last. In Lust, those who failed to control their sexual desires are swept up in an unending storm. The ninth circle, Treachery, is no volcanic lair but a frozen wasteland where the three-headed Dis — frozen in a lake of his own tears — chomps on the corpses of Judas, Brutus, and Cassius.

Dante’s Inferno is full of iconic locations and characters. (Credit: Wikipaintings / Wikipedia)

Dante’s Inferno is full of iconic locations and characters. (Credit: Wikipaintings / Wikipedia)

Where each circle of hell is visually distinct, the nine celestial spheres that make up Paradiso can be rather difficult to tell apart on your first read-through of the poem. Compared to Inferno, the final cantica is often criticized for feeling visually bland. Dante’s over-reliance on motifs of light and brightness — while appropriate considering the setting — can sometimes feel a little repetitious.

Visually, Purgatorio is more striking than Paradiso but still less striking than Inferno. Dante envisioned this section of the afterlife as a giant mountain rising from the southern hemisphere. This mountain is divided into seven rings, themed after the seven deadly sins, and populated by souls who — while not deserving of hell — are not yet worthy of heaven.

Why heaven lacks conflict

Other critics have based their analyses of the cantica’s varying rates of popularity not on visuals but substance, and here too they were able to piece together a number of explanations for why Inferno is more compelling at face value. Reviewing Hollander’s translation for Slate, Robert Baird tried to explain Paradiso’s relative unpopularity as follows:

“For one, it lacks the Inferno’s irony. The characters Dante meets in hell know the circumstances of their sins, but with few exceptions, they can’t see the justice in their punishments. The tension between their knowledge and ours generates a kind of dramatic irony familiar to modern readers: the irony of the unreliable narrator.”

The fact that we fail to appreciate the plain and simple beauty of heaven is itself a sign that we, too, remain stuck in Inferno and that we need Dante to show us the way.

Here, Baird touches on what is perhaps the most common criticism aimed at Paradiso: its inherent lack of drama. These things, while overabundant in hell, can by definition never arise in heaven. Anger, violence, envy, greed, pride — all of the negativity from which Inferno and (to a lesser extent) Purgatorio derive their conflict — are absent from heaven.

When, at the start of the final cantica, Dante encounters Piccarda Donati at the lowest of heaven’s celestial spheres, the morally perfect and deeply religious noblewoman gives a fairly accurate taste of what is to come when she tells the poet, “Brother, the power of love subdues our will / so that we long for only what we have / and thirst for nothing else.”

Putting the comedy in Dante’s Divine Comedy

For every person arguing for Inferno’s superiority, more than a dozen Dante scholars lay out why readers should stick to the very end and give both Purgatorio and Paradiso the attention they deserve. First and foremost, the elements which make Inferno interesting — including Dante’s mastery of language — continue to be present in the subsequent canticas.

In a lecture delivered at NYU’s Italian House, Ron Herzman praised Dante’s ability to compose an eclectic mix of characters. Across his journey through the afterlife, Dante not only encounters famous figures like Homer and Julius Caesar but also people who lived in and were known only by his small and contemporary Florentine community.

In Treachery, sinners are trapped in a lake of frozen tears. (Credit: Wikipedia)

In Treachery, sinners are trapped in a lake of frozen tears. (Credit: Wikipedia)

As interesting as Dante’s conversation with larger-than-life historical figures are, it is his encounters with close friends and old foes that strike us as most meaningful. Paradiso, the cantica where Dante is guided by his diseased and unreciprocated lover — the Florentine noblewoman Beatrice — may well be the most personal of all.

At the end of the day, both Purgatorio and Paradiso are indispensable parts of the poem without which the entire narrative would remain unresolved. Dante’s Divine Comedy is called a comedy not because it is humorous — that meaning was not acquired until recently — but because it has a happy ending and depicts a positive character arc that stretches from Inferno into the subsequent canticas.

Imagining paradise

“For whence did Dante take the materials for his hell,” wrote the German philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer, “but from this, our actual world? And yet he made a very proper hell of it. And when, on the other hand, he came to the task of describing heaven and its delight, he had an insurmountable difficulty before him, for our world affords no materials at all for this.”

In hell, we assume a position of moral superiority, looking down over the sinners and the poor decisions that led them to this wretched place. In heaven, as Baird said, Dante is looking down upon us.

While some interpret these lines as a poignant critique of Paradiso, others may find in it yet another defense for the cantica’s literary significance. Namely, the final section of Dante’s epic poem is an attempt to imagine the unimaginable grace of God. By working through the suffering he experienced on Earth, Dante is able to describe convincingly what heaven may be like:

“O grace abounding and allowing me to dare,” wrote Dante as his semi-fictional self approached what he thought was the vision of God Himself, “to fix my gaze on the Eternal Light / so deep my vision was consumed in it! / I saw how it contains within its depths / all things bound in a single book by love / of which creation is the scattered leaves.”

In his aforementioned talk, Herzman mentioned that Dante wrote the poem with a utilitarian intention. Writing in vernacular Italian instead of Latin — the official language of poetry reserved for the upper classes and religious administrators — Dante wanted to share his vision of hell and heaven with the common man, so that he might inspire them to pray and go on their own religious pilgrimage.

Inspiring prayer

This brings us to the last and perhaps the most important argument for why Purgatorio and Paradiso are worth reading: the notion that these two canticas, more than Inferno, inspire readers to become better human beings. As Baird said, the sinners stuck in hell do not see the error of their ways, and as a result, are unable to recognize the justification for their perpetual punishment.

In Purgatorio and Paradiso, the journalist continues, this irony is flipped on its head. In these canticas, it is the reader — sinful and imperfect — who is out of touch with what is happening around them. The fact that we fail to appreciate the plain and simple beauty of heaven is itself a sign that we, too, remain stuck in Inferno and that we need Dante to show us the way.

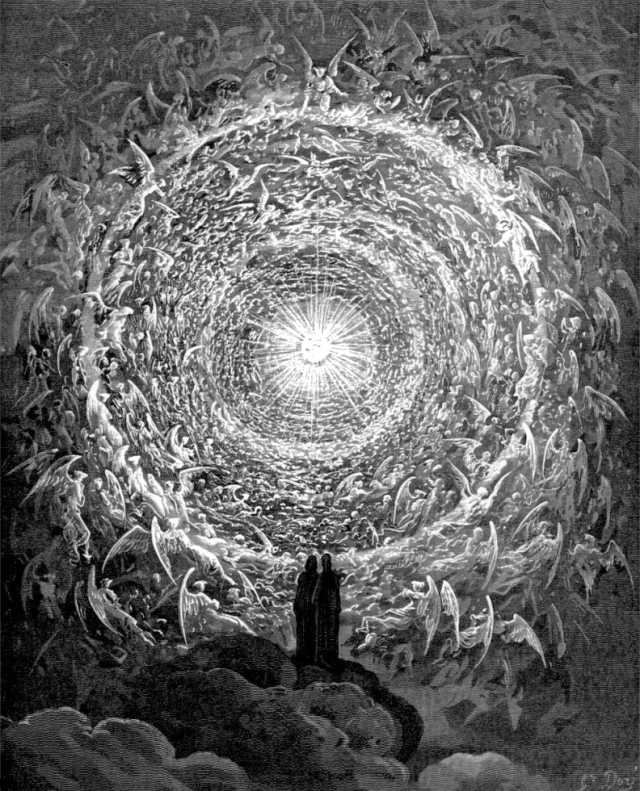

Dante’s audience with God was captured beautifully in Doré’s etchings. (Credit: Wikipedia)

Dante’s audience with God was captured beautifully in Doré’s etchings. (Credit: Wikipedia)

Perhaps one of the reasons why Purgatorio and Paradiso are less popular than Inferno is that the final two canticas draw special attention to our own shortcomings as readers and as people. In hell, we assume a position of moral superiority, looking down over the sinners and the poor decisions that led them to this wretched place. In heaven, as Baird said, Dante is looking down upon us.

Dante wanted his readers to take a critical look at themselves, just as he had done when he was sent into exile from Florence. It was the poet’s hope that they would turn toward God and confess their sins before starting their own journey through hell to heaven. This harsh reality check may have made the final canticas less popular, but that is precisely what makes them so beautiful.