Geopolitical balance of power in chronological sections (Part 1)

We present to your attention a new historical-didactic series of essays on the history of the geopolitical balance of power through the comparison of different chronological cutaways, which allow us to assess the milestones in the formation of civil multipolarism. The idea of the cycle is simple and at the same time non-trivial: to count backwards from the current year 2024 the main anniversaries (3000, 2500, 2000, 1500, 1000, 500 and 100 years ago), in order to demonstrate the action of universal geopolitical regularities on a variety of materials. Each time we will try to find interrelationships between simultaneous conflicts in different regions of the world, thus following in the footsteps of the annual reviews of international relations conducted for three decades by A. J. Toynbee, whose methodology serves as an important, though not exhaustive, model for us.

Who in the last three thousand years have not acquired an understanding

years have not acquired an understanding,

will be dark, foolish, beggars.

In the embrace of everyday life.

J.W. Goethe

Essay 1. Geopolitical order 3000 years ago

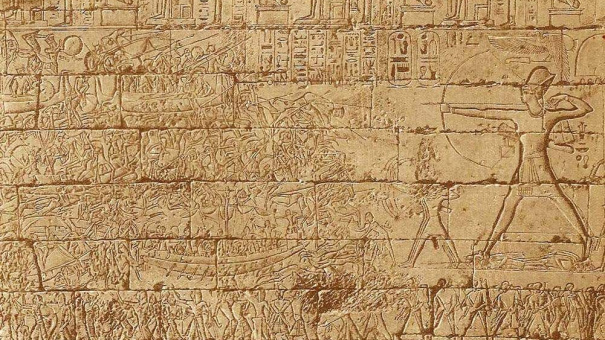

Exactly 3000 years ago, in 977/976 B.C., the Old World was mostly experiencing a “dark age”. The previous civilizations of the Bronze Age had collapsed or extremely weakened and transformed under the blows of the barbarians, whose waves had not ceased their assault for the third consecutive century. This was the historical moment that led to a profound rupture in the system of international relations in the Middle East. Egypt, Assyria, and Babylon weakened enormously under the onslaught of the Aramean nomads, in place of the ancient Hittite kingdom there was a scattering of small late Hittite kingdoms, and only in the midst of this chaos from the Nile to the Euphrates could the State of Israel grow, rise, and strengthen. Exactly 3,000 years ago, the elderly king and storyteller David still sat on the throne of his once conquered Jerusalem, proud of the work he had done. The holy city did not yet have a Temple, but the king's Psalm 99 of thanksgiving already resounded over it:

“Ҳariu l'Adonai kol ҳaaretz. Ivdu et Adonai besimha, bou lefanav birnana. Deu ki Adonai ҳu Eloҳim, ҳu asana, velo anachnu, amo, vezon marjito. Bow shearav betoda, hazerotav biteҳila, ҳodu lo barhu Shmo. Ki tov Adonai, leolam hasdo, vead dor vador emunato.”

“Shout to the Lord, all the earth! Serve the Lord with joy, go before his face with acclamation. Know that the Lord is God, that he has made us and that we are his, his people and the sheep of his flock. Enter into his gates with praise, into his courts with praise, glorify him, bless his name, for good is the Lord: his mercy is everlasting, and his truth from generation to generation.”

The splendour of David's power overshadowed the misery of all his neighbours: Abibaal in Tyre, the Libyan Siamon who had just ascended the Egyptian throne (who was later to become father-in-law to Solomon, David's son, and would annex the Gaza Strip to Egypt), and even more the Babylonian Nabu-Mukin-apli and the Assyrian Ashur-rabi II - utterly insignificant kings, who, although they ruled for three or four decades, could not even defend their capitals from the invasions of the Arameans, whose incursions prevented religious festivals from taking place for years and destroyed the Mesopotamian ritual system. In this way, the chaos of all of Israel's neighbours created a unique century of prosperity for the Jerusalem kingdom of David and Solomon, a geopolitical precedent whose repetition is vainly dreamt of by today's Zionists.

A much more serious change took place this year in China. In 977/976 BC, in a battle with the southern tribes of the Chu kingdom for access to the Yangtze river, King Zhou Zhao-wang fell. His son and successor Mu-wang took the throne, who would rule for more than half a century, also continuing the wars in the periphery. However, Mu-wan's main action was not war at all. He was well aware of the abnormality of the situation: half a century had passed since the overthrow of the Shang dynasty and the conquest of the Shan state by the Zhou, but the old Shan aristocracy still retained influence and three generations of Zhou rulers continued to pray not to their own, but to a foreign heavenly ancestor, Shang-di. The threat of a Shan restoration could have erupted at any time. Any flood or celestial sign could have signaled a denial of the Chou's claim to the celestial mandate.

Under these circumstances, Mu-wang decided to take an unprecedented step, about which later Confucians preferred to remain silent. But even modern historians for a long time failed to understand what had happened 3000 years ago in the Huang He bend. Soviet historians at the time of the conflict with the People's Republic of China drew the following image in their imagination: Mu-wan's warriors were standing up to their waists in a millet field and shouting the slogan: “We must continue the work of Wen-wan and Wu-wan until our state becomes world-wide!”.

Common sense dictated that such a globalist slogan simply could not exist in 976 BC. In fact, a review of the sources revealed the truth. This sentence is a mistranslation of one line of an inscription on a ritual metal pan, “Shi Qiang Pan”. This line is very obscure to understand, containing two out-of-use hieroglyphics, but nevertheless its meaning is as follows: “Son of Heaven inherited and continued the qualities of Wen and Wu, bringing order to the universe (cosmos) to its furthest limits”. It thus refers to Mu-wan's ritual role as king of the world on its polar axis, as the immovable engine that gives harmony to the entire cosmos. At the same time, “Wen and Wu” in this record can be understood either as the names of the founders of the Chou dynasty - Mu-wang's ancestors - or with the literal, nominative meaning of these words: “wen” 文 - virtue, “wu” 武 - punishment.

In other words, Mu-wan claimed to be the bearer of the divine qualities of virtue and punishment. He appealed to the celestial God Shang-di with a complaint against the spirits of the Shang ancestors; according to the king, the God responded by ordering the spirits to abandon the Zhous and obey the ancestor of the Zhou dynasty, Hou-ji (Uncle Millet, whose monuments still stand in China).

After announcing this change, Mu-wang immediately deepened the religious reform, cancelling separate naming forms for the spirits of the dead, replacing the deep metal ancestor reliefs (tao-te) on bronze vessels with flat, ribbon-like geometric ornaments. The shape of the vessels changed and the astronomical cults changed. Rumors spread that Mu-van had flown in a dream to the celestial paradise from the goddess Sivan-mu and had eaten the pears of immortality there. And the joyful peasants ran through the millet fields in spring, singing:

“Mgra's mra’ gwii tiiv,

Laps gwae‘ tret gwang,

Srums gro’ ze‘ l'in,

Gwang pheis dian krang”

“Now Mu-wang approves the government of Chou,

The wise kings have been heard in previous generations,

The three kings of Chou are now in heaven,

Their successor - in the capital of vast domains.”

Strictly speaking, the religious history of classical ancient China begins with the reforms of Mu-wang, just as the religious history of classical Old Testament Judaism begins with the reforms of his contemporary David. And all this was made possible by a change in the geopolitical order that occurred exactly 3000 years ago, when Israel temporarily and unstably became the world's second power pole, along with China.