Russia-India-China (RIC) partnership can focus on Africa following Lavrov’s call

Russia’s foreign minister, Sergey Lavrov, has recently called for the revival of the Russia-India-China (RIC) dialogue.

Speaking at a Eurasian security conference on May 29, Russia’s top diplomat declared Moscow’s genuine interest in rebooting the Russia-India-China (RIC) format.

“I would like to confirm our genuine interest in the earliest resumption of the work within the format of the troika -- Russia, India, China -- which was established many years ago on the initiative of (ex-Russian prime minister) Yevgeny Primakov, and which has organised meetings more than 20 times at the ministerial level since then, not only at the level of foreign policy chiefs, but also the heads of other economic, trade and financial agencies of the three countries,” Russian news agency TASS, quoted Lavrov as saying.

The timing of Lavrov’s pitch was significant. After a gap of five years of border tensions and extended rounds of talks between Indian and Chinese military officials, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi and Chinese President Xi Jinping had finally met. The thaw was achieved in Kazan on the sidelines of the BRICS summit. Ahead of the leader-level interaction, Indian and Chinese troops had disengaged from their forward deployments that took place in May 2020, opening the door for the seminal meeting.

“As of today, as I understand, an understanding has been reached between India and China on how to ease the situation on the border, and it seems to me that the time has come for the revival of this RIC troika,” Lavrov stressed.

Lavrov’s proposal also came amid a major transition of the global system towards multipolarity. The Trump administration which had displaced Biden administration in Washington, has rejected a globalist foreign policy of trying to dominate the world, which has included pursuit of the regime change doctrine. The steady erosion of the globalist Deep State in the US, and Trump’s inward-looking focus to Make America Great Again (MAGA) template has opened the geopolitical space to other poles of the global system, especially Russia, India, and China, to expand and consolidate their polar bandwidth.

Trump’s tariffs targeting both China and India are also encouraging the two Himalayan neighbours to once again explore geo-economic opportunities with each other.

But in tune with Lavrov’s call for the revival the RIC format, the troika, under the changed circumstances, can now look for joint trilateral opportunities, especially in Africa, as part of an accelerated engagement with the Global South.

What can Russia, India and China can bring to the table in their trilateral engagement of Africa?

For starters, all three countries have engaged the entire continent, but with a stronger footprint in specific geographies. This is not new. In fact, each of three countries have had a longstanding relationship with Africa. During the Cold War, the former Soviet Union was majorly engaged in Africa’s successful armed liberation struggles including in the former Portuguese colonies of Angola, Mozambique and Guinea Bissau. China too was engaged in supporting armed liberation struggles, but was arguably best known for building the Tazara railway connecting mineral rich Zambia to the Indian Ocean through Tanzania. As a pioneer of the Nonaligned Movement (NAM), India played a seminal role in bringing Africa into the fold of NAM. This happened during 1955 Bandung Afro-Asian conference in Indonesia. India was also engaged in soft-power projects in supplying Africa with essential medicines to manage the HIV pandemic, apart from training thousands if not more, Africans in its universities, military institutions and research institutions.

Under the RIC template, the three countries can collectively leverage their positive post-colonial legacy with the continent on an unprecedented scale during the multipolar era.

Before such joint forays can begin, it is important to grasp that Africa has also significantly mutated. Under its Agenda-2063 vision, it has defined its own roadmap that can steer its rise in the digital era. It is therefore important that the RIC-Troika docks with Agenda-2063 and not impose any strategic blueprint of its own, in this exceptionally vibrant continent.

What is Agenda-2063?

Launched in Adis Ababa in January 2015, Agenda 2063 is a 50-year plan to holistically transform Africa, along with embellishing the continent’s unique cultural identity.

Apart from eradicating poverty within one generation, Agenda-2063 has an ambitious political agenda. This includes political integration, resulting in formation of a pan-African confederation based on principles of democracy and justice as well as regional collective security. Besides, it seeks to foster Africa’s unique cultural identity, driven by “African renaissance.” Finally, it calls for gender equality as well as political independence from foreign powers, echoing a powerful sentiment in Africa of liberating itself from its sordid colonial history.

To usher prosperity, Agenda 2063 has earmarked transformational infra-projects, including setting up a high-speed train network that would connect all African capitals and commercial hubs, and harnessing the waters of the mighty Congo River.

Besides, the Agenda-2063 plan hopes to set up an African Continental Free Trade Area. On finance, it visualises an African Investment Bank, a Pan-African Stock Exchange, an African Monetary Fund, and an African Central Bank. Its 360-degree blueprint also caters for establishing a Great African Museum, which would showcase Africa’s proud cultural heritage and promote Pan-Africanism. An Encyclopaedia Africana--an authoritative resource on the authentic history of Africa and African life—is also to be published as feedstock for sketching the continent’s progressive post-colonial narrative.

Russia has already declared its support for Agenda 2063, embedding it in the Russia-Africa Partnership Forum Action Plan (2023–2026).

“This Action Plan outlines priorities and measures to tap the potential of the Russia-Africa partnership in areas of mutual interest, taking into account the African Union’s Agenda 2063: The Africa We Want and plans to implement it, as well as other documents in the field of cooperation between Russia and Africa,” a Kremlin readout said.

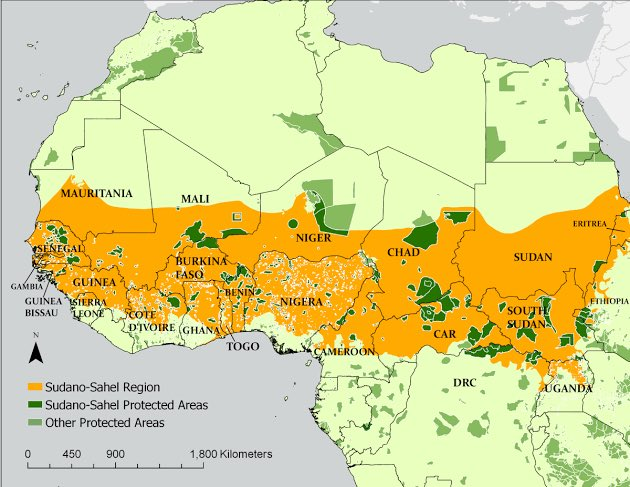

In engaging with Africa in the multipolar setting, Russia has been especially focusing on the Sahel region-stretching from the Atlantic coast in the West and Indian Ocean in the east—along with its periphery. The semi-arid region which includes Senegal, Mauritania, Mali, Burkina Faso, Niger, Chad, Sudan, and Eritrea divides the Sahara desert to the north and the savannas to the south.

Map of Sahel

In engaging with the area, Russia has leveraged its strengths in provisioning energy security, food security and military security. Regarding energy, Russia has signed nuclear cooperation agreements with 15 African countries, including Burkina Faso, Zimbabwe, Mali, Rwanda, Egypt, and South Africa. For instance, Russia is constructing the El Dabaa Nuclear Power Plant, financed through a $25 billion loan.

El Dabaa Nuclear Power Plant

It is expected to add 4,800 MW to Egypt’s power grid. In Rwanda the Russian energy giant Rosatom has tied up to build a Nuclear Science and Technology Centre, focusing on research, healthcare, and agriculture. Russia is also a major weapon supplier having signed military-technical cooperation agreements with at least 43 countries. Within the ambit of security, Russia intends to develop a Regional Security Hub in Burundi—a centrally located nation in the Great Lakes region, making it an ideal base for coordinating crisis management efforts. The centre is expected to provide military training, strategic planning, and logistical support to allied nations.

Russian media reports say that Moscow hopes to establish a based in the Central African Republic (CAR).

The choice of landlocked CAR is significant, as the country located in the heart of Africa, sharing borders with Chad to the north, Sudan to the northeast, South Sudan to the east, Democratic Republic of the Congo to the south, Republic of the Congo to the southwest, and Cameroon to the west.

In other words, CAR is located at the crossroads between Central and East Africa, making it a potential hub for regional trade and connectivity.

Divided between the Ubangi River basin, which flows into the Congo River, and the Chari River basin, which connects to Lake Chad CAR connects with key waterways that are crucial for agriculture and transportation in the region.

Central African Region

Besides, Russia has been providing humanitarian assistance, including 709.5 tons of aid to Burkina Faso and 20,000 tons of wheat to Niger. Besides, Moscow has been offering scholarships and educational programs to African students on a significant scale.

On its part, India has emerged as primary engine generating impressive soft power in Africa, focusing on agriculture, energy, pharmaceuticals, and infrastructure. According to recent reports, India aims to double its trade with Africa to $200 billion by 2030, from a $100 billion base in 2022.

India’s outreach towards Africa takes the cue from Agenda-2063. India is leveraging its strengths in Information Technology, healthcare, renewable energy, agriculture and education, where it has deployed digital tools for distance education.

In healthcare, India has played a significant role in improving healthcare in Africa through medical infrastructure development, pharmaceutical exports, and digital health initiatives. Some key contributions include affordable medicines, especially providing low-cost generic drugs. India has also provided medical training and capacity building for African healthcare professionals, enhancing local expertise. Besides, it has provided remote healthcare access using digital platforms such as e-AarogyaBharati (e-VBAB) Network, which facilitates remote medical consultations and connecting African healthcare specialists with their Indian counterparts. Besides, organisations such as the India Africa Medical Commission (IAMC) connect the Indian and African healthcare eco-systems to foster collaborations. In 2023, India’s pharmaceutical exports to Africa stood at $3.8 billion.

In the IT domain, India has shared its experience with Africa in the Digital Public Infrastructure domain. India has shared its expertise in Unified Payments Interface (UPI), CoWIN, and Open Network for Digital Commerce (ONDC) to enhance Africa’s digital ecosystem. Regarding Fintech & Financial Inclusion, India has helped African nations improve digital banking, mobile payments, and financial accessibility.

Digital India

Other key sectors of collaboration include transfer of seed technologies and ago-processing methods, automobiles especially two-wheelers and affordable cars. Regarding Renewable Energy, more than 20 African countries are participating in the International Solar Alliance (ISA), strengthening India-Africa energy partnership.

India’s strength in Africa is its diaspora, enabling New Delhi to leverage natural connections with the host country’s elites. For instance, 1.3 million people of Indian origin reside in South Africa, 994,500 in Mauritius, 220,000 in Mauritius and 100,000 in Kenya.

Unlike India’s focus on soft-power, China has concentrated on big infrastructure projects, which can transform Africa.

The Chinese have strategically invested around $700 billion in Africa, in a 10-year span that began in 2013, soon after Xi Jinping assumed charge as the General Secretary of the Communist Party of China (CPC). Overall, China has built over 12,000 kilometres of road and railway tracks, around 20 ports, and more than 80 power facilities in Africa, according to CCTV, China’s state broadcaster. Its flagship projects include the railway linking Mombasa, Kenya’s port city to Nairobi, the capital, and Naivasha, a fertile farming hub in the country’s Central Rift Valley. There are reports that this line from Naivasha will now be further extended by 475 kilometres to Malaba on the Uganda border.

Nairobi to Mombasa railway

Among the strategic projects that China has undertaken under BRI, Djibouti’s Doraleh multi-purpose port stands out. Incidentally, this investment that took place after China, in 2016, had established, at a cost of $590 million, its first permanent overseas naval base in Djibouti—a strategic location between the Red Sea and the Gulf of Aden.

Of late, the Chinese have focused on clean energy projects following criticism that China’s coal fired plants announced earlier in Africa were causing severe environmental damage.

Consequently, Chinese companies have recently stepped up their investments in renewable energy projects. For instance, in Nigeria—Africa’s powerhouse on the Atlantic coast—the Chinese Exim Bank is reportedly providing 85 per cent funding for the Mambilla hydroelectric plant—a $4.9 billion undertaking.

Similarly, the Chinese are pitching in $ 533 million for the expansion of Zimbabwe’s Kariba Hydroelectric Power Station.

In tune with focus on clean and digital economy, China is investing heavily in Africa’s deposits of lithium, cobalt, and copper—the feedstock for its booming electric vehicles industry.

For instance, in Zimbabwe—a country that has been on its radar for a long time—China’s Sichuan PD Technology Group has been investing in the Kamativi Lithium Mine. A processing plant, which is part of the project will produce spodumene concentrate--a key material for batteries.

Kamativi lithium mine in Zimbabwe

The Chinese have also been scouting for lithium in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), Namibia, Mali, and Ethiopia.

Similarly, China is pitching huge resources to secure copper, whose demand has surged because the metal is heavily used in electric vehicle engines.

That includes a $1.9 billion deal, reached last year, by state-owned MMG to buy the Khoemacau mine in Botswana, one of the world’s largest copper mines.

In July, Chinese firm JCHX Mining Management agreed to buy Zambia’s indebted Lubambe copper mine for just $2.

According to the American Enterprise Institute, China invested $7.8 billion in mining in Africa, in 2023 alone.

While individual initiatives abound, the RIC can synergise, coordinate, and expand individual forays on a pan-African scale. To achieve that, the RIC may need to structurally evolve by establishing an Africa committee within the RIC framework that can become the main hub of trilateral partnership in the continent. An additional RIC think tank alliance, connected to an advisory and consulting services wing, specialising on Africa may also help to add ballast to the grouping.

The RIC can also adopt a 3+1 formula, where the troika internally consults with each other to define, detail and coordinate its engagements with a specific African country or organisation. Here, institutions engaged in long-term planning such as India’s National Institution for Transforming India (NITI) Aayog, the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC) of China and Russia’s Ministry of Economic Development and State Council, can become the primary nodes, providing specific inputs for 3+1 initiatives in Africa.

Finally, from an ideological perspective, it is imperative to understand that the RIC initiative was conceived by the late Primakov as an engine to foster a multipolar world. The initiative therefore must dock with the initiatives and vision of the BRICS, which is the primary driver of post-west, though not anti-west, multipolar world order.