China: Greater Eurasia Scenarios

The Chinese Security Circle

China’s security can simply be summed up to the retention of stability along is internal and external borderlands, with the understanding being that peripheral destabilization usually precedes domestic disturbances. The ethnic Han are now an overwhelming supermajority of the country, but they and the Chinese Communist Party still need to contend with a handful of potentially troublesome minority groups spread out over a large geographic space and whom some of their members are highly susceptible to exploitative outside influences. Additionally, there’s also the long-term threat that the historical memory of some regions and peoples could be manipulated to return to the fore of their conscientious decision making, which in practical terms means that even ethnic Han or the local minorities of areas previously not affected by separatist sentiment could find themselves embroiled in these problems. The Chinese Security Circle extends in a circle all along the heavily populated eastern seaboard that serves as the core of the country and its historical civilization.

Manchuria:

Beginning in the northeast, the first area of future concern is “Manchuria”, whose people have a very well-known history of having ruled over China during the Qing Dynasty. The Manchus no longer constitute a relevant percentage of the population, but the historical memory of the region could threateningly be manipulated against the authorities in promoting a hostile anti-center (Beijing) agenda. It’s a far-out scenario and one which probably won’t ever take any substantial shape or form, but it nonetheless deserved to be mentioned as an unchanging vulnerability (however unlikely) to China’s security, especially since the Japanese exploited this seemingly impossible eventuality in the 1930s by forcefully establishing their puppet state of “Manchukuo” in the region. Although the geopolitics times have indeed changed since then, the concept of a distinct “Manchurian” identity that could be manipulated against Beijing will always remain a problem, however unlikely its return physical manifestation may be.

The Koreas:

Millions of Koreans live in the Manchurian borderland near North Korea, and in the event that Pyongyang collapses or anything similarly disruptive occurs, then even more Koreans will swarm across the border if they can’t be stopped ahead of time. Should North and South Korea ever reunite, then the Koreas might one day become strong enough to present a mild competitor to China, being between it and Japan and more than capable of managing affairs between them to its own benefit.

Most worrying to Beijing, though, would be whether American military personnel would remain in the country, which is very probable, and whether the newly reunited country will seek to manipulate the Korean community in China’s Manchuria for some yet-to-be defined strategic purpose. In the present day, however, South Korea is turning into a worrying problem for China because of the US’ THAAD “anti-missile defense” deployment there, which undermines Beijing’s nuclear second-strike capability.

East China Sea:

The island dispute with Japan is important for China not just for historical-normative reasons, but because these territories are its gateway to the Western Pacific. From the Japanese perspective, they can thus be used to ‘contain’ the Chinese navy in a ‘safe’ and ‘manageable’ zone of A2/AD , thus explaining China’s urgency in wanting to break out of this ‘cordon sanitaire’.

South China Sea:

The nine-dash line might seem overly ambitious and historically questionable, but from a strategic sense, they’re definitely warranted. China doesn’t want to “impede” trade in the South China Sea like the US and its affiliated information organs accuse it of, but to safeguard it because most of the country’s energy imports and all of its European, African, and Mideast trade in generally come from this direction.

It might be controversial that China is “building islands” on the territories that it claims as its own, but realistically speaking, had China not taken these moves, then the US and/or its regional allies would have beaten Beijing to it in order for the unipolar world to do precisely what it accuses China of allegedly doing, which is trying to “control” and “impede” trade.

Because of the complications that the US has created in the South China Sea and the unreliability of this waterway in the event of war or some other unfortunate event, China is steadfastly working to build a series of overland Silk Roads to guarantee its dependable access to the high seas and away from the easily clogged chokepoint of the Strait of Malacca.

Yunnan and Indochina:

China’s southernmost mainland territory is an eclectic mix of different tribes and ethnicities very closely related to the peoples of Indochina. Mountainous Yunnan is geographically well-defended from conventional assaults, but is vulnerable to asymmetrical ones such as penetration from drug trafficking gangs, “weapons of mass migration”, and insurgent infiltrators. Vietnam could understandable pose a real threat in the event that hostilities boiled over with it in the South China Sea and it launched a sneak or retaliatory ground attack to catch China off guard, but it’s more likely that Myanmar and perhaps even one day Laotian insurgents and refugees might spill over into the southern Chinese border and destabilize the harmonious balance of identities in the most diverse region of the country.

“Greater Tibet”:

The historic-cultural region of Tibet is much larger than its eponymous province, which itself represents only one of its three regions, U-Tsang. The eastern part of this administrative entity and the western portion of Sichuan comprise what was once known as Khan, while Qinghai mostly corresponds to Amdo. Although lightly populated, these three spaces occupy a vast region of land replete with irreplaceable strategic value, such as the Tibet Autonomous Region’s control over Asia’s 7 main waterways that collectively supply almost half of the world’s population by downstream extent. This is the real reason why the US and India want an “independent” Tibet, which is to seize resources by proxy and use them to control the rest of China, to say nothing of the South and Southeastern Asia.

Xinjiang:

Some of the people in this Turkic-populated Muslim region of China have been fighting for “autonomy” or “independence” from China, covertly backed up by the West and its GCC allies in order to splinter the resource-rich part of the country away from Beijing and create a hardcore Salafist state in the pivot region between Central Asia, Siberia, Han-majority China, and Tibet. Xinjiang is also important because it’s where China carries out a lot of its space flights, so the region has added strategic significance aside from the geopolitical.

The Chinese state maintains tight control over the region even though reports about its “suppression” of local culture and religion are totally exaggerated, but the point is that terrorists have no chance at the moment to recreate the Daesh-like circumstances of carving out their own caliphate in the desert.

Instead, most of their activity will likely remain contained to the cities, though that doesn’t by any means make then less effective. On a related note, the Kush Caliphate scenario that was described when speaking about Central Asia is very pertinent here, and it’s for this reason why China advanced the Quadrilateral Cooperation and Coordination Mechanism between itself, Tajikistan, Afghanistan, and Pakistan recently in order to preempt the emergence of a nearby training ground for more Xinjiang terrorists.

Inner Mongolia:

Not many people live in the large territory of Inner Mongolia, but the region is still very prized to Beijing for two reasons. Firstly, it is extraordinarily rich with rare earth minerals and coal, but secondly, it’s an ethno-historic gateway to leveraging more influence towards Mongolia proper. China has no territorial claims against its northern neighbor, but the point is that Inner Mongolia can serve as a cultivator of soft power influence, especially since there are more Mongols living here than in their namesake country.

The threat, though, would be if these Mongols (which are around 1/7 of the population of ~24 million total people) ever came to be “aware” of their nationality through NGO and other outside manipulation, which might then turn China’s whole Mongol strategy against it. There’s no practical way that Inner Mongolia would ever “reunite” with Mongolia or pose a serious threat to China, but it could turn into a minor headline-grabbing irritant that, when combined with other simultaneously ongoing peripheral borderland disruptions, might contribute to pushing the situation past the tipping point.

Overspill Threats

There are three bordering countries whose domestic breakdowns could lead to an overspill of asymmetrical threats into China proper. Not counting the terrorist safe haven and training grounds in Afghanistan, these are:

Kyrgyzstan:

The destabilization-prone Central Asian state might fully collapse if it undergoes a third “revolution”, thus making possible the formation of a transnational “Kush Caliphate” in the mountainous region between itself, Tajikistan, Afghanistan, and Pakistan. Even if this doesn’t happen in the way that it’s projected, the Islamic extremism of the Fergana Valley might find a way of slithering through the border into Xinjiang, or conversely, become a much closer and therefore dangerous training camp than Afghanistan ever could be (provided of course that the situation isn’t stabilized by domestic or potential outside [CSTO, possibly in joint operation with China] means).

Nepal:

The former Hindu Kingdom now teeters close to another civil war as it the northern highlanders compete with the southern lowlanders over the federal delineation of the country. Violence here could produce not only thousands of refugees that stream into China, but also a dangerous void of destabilization that could serve to obscure the training of any Tibetan-destined “Buddhist” terrorists, or even become a magnet for some in neighboring Tibet to travel to. Furthermore, Indian-trained Tibetan insurgents could use the country as a springboard for infiltrating China by exploiting Nepal’s lack of law and order at this time in order to stream into the People’s Republic under the cover of being “refugees”.

Myanmar:

Although the fighting in Shan and Kachin States has largely subsided compared to what it had been during previous times, like it was explained in the scenario descriptions for ASEAN, fighting could renew in the future if the federalization talks (Panglong 2.0) break down and the insurgents return to the field. Additionally, even if they’re successful, they might lead to a noticeable diminishment of the central government’s military presence along the country’s periphery, especially if clauses are included to allow federal entities broad autonomy in their security affairs. Remembering how it’s predicted that Shan State might devolved to form an unworkable ‘federation within a federation’, it’s entirely possible that another eruption of conflict will inevitably happen with time, though this time complicated by the fact that a checkerboard of statelets will now be created over which competing Great Powers are now vying. Drugs, insurgents, and “refugees”/immigrants are the greatest threats in this scenario.

A Federation Of Megacities

Strategist Parag Khanna argues in his new book “Connectography” about how China is rapidly turning into a ‘federation of megacities’, procuring a conceptual map which convincingly illustrates this point. Provided that the country continues to move in this direction, it’ll remain to be seen how this will practically and legally change its governing structure, as well as what the effects of the geographic division of the country into a ‘federation’ of central-eastern megacities and peripheral settlements will be.

One possible scenario is that the separatist movement in Hong Kong (itself a key member of the “federation of megacities”) could serve as a future pretext for a chain reaction of secessionism among its mainland coastal counterparts if they’re able to establish a strong enough independent identity to do so, though this of course requires a long-term investment in skilled and coordinated NGO support in preconditioning the masses to this point.

On a related tangent of “megacity” separateness, the existing socio-linguistic division between ‘northern’ and ‘southern’ China in Mandarin and Cantonese halves will have to be monitored for signs of regionalism along the lines of one of the scenarios which was previously predicted for India.

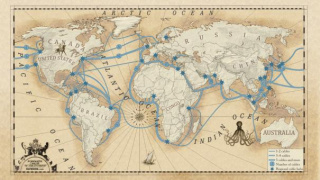

The New Silk Roads

Officially termed the One Belt One Road plan but colloquially referred to in the international press as The New Silk Roads, China’s global strategy is to tie itself together with all of its partners in a complex system of mutual economic interdependence that can provide a sustainable outlet for its domestic overcapacity. There are also more strategic elements to this as well, such as avoiding the Strait of Malacca and the South China Sea. Looking at the chief mainland routes that China has explored, whether they’ve only been floated around, were former visions that didn’t pan out, or are being presently advanced in some tangible form or another, they are as follows:

The ASEAN Silk Road:

Laos-Thailand-Malaysia-Singapore

Myanmar Silk Road:

Myanmar

BCIM Corridor:

Myanmar-India-Bangladesh

China-Pakistan Economic Corridor:

Pakistan

Central Asian-Persian Silk Road:

(undefined, but likely including the following countries)

Kazakhstan-Uzbekistan-Turkmenistan-Iran

Eurasian Land Bridge:

Kazakhstan-Russia-Belarus

Balkan Silk Road:

Greece-Republic of Macedonia-Serbia-Hungary (possibly through –Slovakia-Poland-Lithuania-Latvia-Estonia-Russia [St. Petersburg]).