What about the Workers? A Libertarian Answer

I was called this morning by the BBC. It wanted me to comment on the claims that Sports direct, a chain of sports clothing shops, mistreats its workers – keeping them on zero-hours contracts, sometimes not paying them even the minimum wage, scaring them out of going sick, generally treating them like dirt. Would I care to go on air to defend the right of employers to behave in this way? I am increasingly turning down invitations to go on radio and television, and this was an invitation I declined. I suggested the researcher should call the Adam Smith Institute. This would almost certainly provide a young man to rhapsodise about the wonders of the free market. My own answer would be too complex for the average BBC presenter to understand, and I might be cut off in mid-sentence.

Here is the answer I would have taken had I been invited to speak on a conservative or libertarian radio station on the Internet.

First, it is a bad idea to interfere in market arrangements. Sports Direct is in competition with other firms. Making it pay more to its workers, or to give them greater security of employment, would require it to raise prices and make it less competitive. A general campaign against zero-hour contracts and low pay would raise unemployment. In even a reasonably open market, factors of production are paid the value of their marginal product. Establish a minimum price for labour above its clearing price, and those workers whose employment contributes less than this to total revenue will be laid off. If I felt more inclined than I do, I could produce a cross diagram to show this. The downward sloping curve would show diminishing marginal productivity, the upward the supply of labour at any given price. The point of intersection would show the clearing price. Draw a horizontal line above this clearing price to show the minimum allowed price, and you can two further lines from where this intersects the curves to create a box showing the unemployment that would result. I leave that to your imagination. Or here is a representation I have found on-line:

Second, intervention of this sort tends to benefit larger firms at the expense of smaller. Sports Direct might be able cope with the resulting increase in labour costs by replacing labour with capital, or by squeezing its suppliers. The result would be increased market concentration, and this might not be to the benefit of workers.

Third, let us suppose that intervention for the alleged sake of the workers was actually to their benefit. It would still be undesirable, so far as it made the State the arbiter of fair practice and raised the prestige of the State still higher – thereby justifying still more interventions. I do not believe that any state intervention for the alleged benefit of ordinary people has been other than to enrich or empower some special interest group. But every state has its tame intellectuals to cry up whatever it does as steeped in the public good.

So far, I could pass – age and appearance always excepted – as one of Madsen Pirie’s young men. The difference is that I do not see the present state of the British labour market as the best of all possible worlds. I repeat – it is a bad idea to interfere in market arrangements. But we should look beyond the cross diagram I have described. Market arrangements do not emerge in a vacuum. Their forms are determined by legal and institutional arrangements that can be judged in terms of how they contribute to the national wellbeing, and that, where they fail this test, ought to be changed. Here are my further comments.

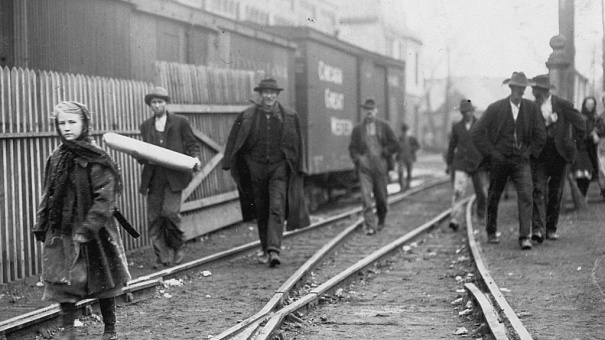

First, the bottom end of the labour market is distorted in ways that force workers to present themselves to firms like Sports Direct. Many years ago, when I was a student, I was in want of money, and so I worked in London as a mini-cab driver. All I needed was a car and driving licence and a certificate of hire and reward insurance. I paid a weekly rent to the cabbing company, and worked what hours I found convenient. I found myself working beside a milkman who wanted money for his daughter’s wedding, and a bus driver who was saving up for a deposit on a house, and men who were unable to find work anywhere else. When I no longer wanted the work, I stopped paying my rent and walked away. The market is nowadays regulated and licensed. Costs of entry can be as high as £60,000. Once in the market, these costs are handed on to the passengers, but initial entry has costs that deter most ordinary people.

I could go through dozens of other occupations that are effectively closed. But the point I am making is that, for most people, there is no alternative to paid employment, at whatever rates of pay.

Second, mass-immigration imposes terrible costs on the working classes. Think again of my cross diagram. Flatten the supply curve until it is almost perfectly elastic, and you have something like most labour markets at the bottom end. When the clearing price of labour is less than the minimum wage, that is what will be paid. If there is some enforcement of the minimum wage, then overall wage costs will be lowered by denying customary benefits like tea breaks and sick leave.

Third, there has been a consistent bias, at least since 1979, against any kind of enterprise that may give comfort and dignity to the working classes. In part, patterns of comparative advantage have shifted against mass-manufacturing in this country. In part, the behaviour of the trade unions after 1945 made much manufacturing unviable. But it is also a fact that policy since 1979 has been to promote the service sectors of the British economy. This has been greatly to the advantage of anyone who can get into the financial sector. For those at the bottom, it means semi-casual labour in places like Sports Direct. Indeed, I am not convinced that the patterns of comparative advantage I mention are as impersonal as changes in the weather. Globalisation is not free trade in the sense conceived by the early liberals, but is managed trade – regulated at almost every point in the supply chain to produce a determined outcome.

My answer, then, to the BBC’s question is not to lean on Sports Direct or other firms of its kind, nor to celebrate the glories of our alleged free market. It is instead to insist on non-intervention in market arrangements, while taking a strongly critical look at the wider arrangements within which market activity takes place. I trust you will agree that this would not have been the sort of answer appropriate to the average BBC discussion, and that I was right to decline that invitation.