Why global value chains should be called global poverty chains

Global value chains (GVCs) “boost incomes, create better jobs and reduce poverty,” according to the World Bank. Since the collapse of the Eastern Bloc in 1991 and the reintegration of China into the global economy, world trade has become increasingly organized through GVCs. For example, the components and inputs for Apple’s iPhone, an icon of contemporary capitalist globalization, are made by millions of workers in over fifty countries.

Transnational corporations (TNCs) — labeled “lead firms” in the academic literature — established GVCs as part of their competitive strategies, outsourcing existing work or starting up new activities in countries where labor costs were cheap. State managers across the Global South increasingly gave up on establishing integrated domestic industries and sought instead to enter GVCs as component suppliers. Today, over four hundred fifty million workers are employed in GVC industries.

Many prominent figures suggest that these systems of production and distribution represent radically new development opportunities. As the former secretary general of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), Ángel Gurría, claimed:

Everyone can benefit from global value chains . . . encouraging the development of and participation in global value chains is the road to more jobs and sustainable growth for our economies.

The academic Gary Gereffi, the intellectual father of GVC analysis, asserts that development across the Global South requires supplier firms “linking up with the most significant lead firm in the industry.”

In reality, GVCs are a great boon for some of the world’s biggest companies, but not for their workers. It would be more accurate to describe many GVCs as global poverty chains.

Global Poverty Chains

Arecent legal case has exposed how Burmese migrant workers in Thai factories, producing jeans for the mega UK retailer Tesco, experienced forced labor, subminimum wage pay, and abusive working conditions. Between 2017 and 2020, these workers made jeans, denim jackets, and other clothes for VK Garment (VKG). They are suing the company — the UK’s biggest retailer, and the world’s ninth-largest by revenues — for alleged negligence and unjust enrichment.

Workers typically labored from 8 a.m. to 11 p.m. with one day off a month. Sometimes they were forced to work for twenty-four hours a day to fullfil large orders. While the Thai minimum wage at the time was £7 for an eight-hour day, most workers received less than £4 a day. Workplace injuries and abuse by managers were common.

The migrant workers relied upon VKG for their immigration status, increasing their vulnerability to managerial bullying and wage theft. VKG accommodation was dirty and overcrowded. When one woman asked to be paid the Thai minimum wage, managers called her a dog, and told her: “If you don’t want to work at the factory any more, you can get out.” Tesco made profits of over £2 billion in 2020.Eighty percent of export processing zones paid wages below the national minimum wage.

The experience of extreme exploitation for these Burmese workers is common practice in global value chains. GVCs are organized by lead firms such as Tesco precisely so they can grab the lion’s share of the value created by workers, leaving the latter with next to nothing.

Structures of Exploitation

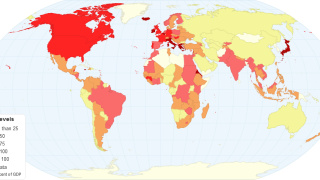

GVCs sprang up in the same historical moment that neoliberalism became politically dominant across the world. Export processing zones (EPZs), where foreign capital enjoys import-export tax exemptions and access to cheap, often nonunionized labor, fueled the rise of GVCs. They increased from seventy-nine in twenty-five countries in 1975 to over thirty-five hundred in one hundred thirty countries by 2006. By then, EPZs employed around sixty-six million workers.

The International Labour Organisation found that some 80 percent of EPZs paid wages below the national minimum wage. EPZ-type labor conditions have spread across national economies, handing corporations massive profits at the expense of workers. As United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD)’s 2018 Trade and Development Report puts it:

The rise in the profits of top TNCs accounted for more than two-thirds of the decline in the global labor income share between 1995 and 2015. Therefore, although the rising share of the profits of top TNCs has come at the expense of smaller enterprises, it has also been strongly correlated with the declining labor income share since the beginning of the new millennium.

Take the example of Apple’s high-tech iPhones. According to GVC supporters, workers should benefit from employment in high-tech sectors because of their high productivity. Yet far from spreading the gains of GVC-based globalization, the production of these phones is based upon poverty wages and harsh working conditions. Apple’s profit for the iPhone in 2010 constituted over 58 percent of its final sale price, while the share going to Chinese workers was just 1.8 percent.

Components for the iPhone are produced by megafirms such as Foxconn and the less well known but equally exploitative Pegatron. Labor conditions in these factories are dictatorial and abusive. Terry Gou, chief of Hon-Hai, Foxconn’s parent company, once remarked: “Hon Hai has a workforce of over one million worldwide and as human beings are also animals, to manage one million animals gives me a headache.” It is thus no surprise that the Foxconn labor regime is characterized by regular and consistent humiliation of workers.Apple’s profit for the iPhone in 2010 constituted over 58 percent of its final sale price, while the share going to Chinese workers was just 1.8 percent.

In the Pegatron factories in Shanghai, China Labor Watch reported how “workers must assemble 450-500 motherboards per hour.” Over half of its employees worked over ninety hours overtime a month because “their base wages . . . cannot meet the local living standard.”

Bogus Measurements

Pay in factories such as Foxconn, Pegatron, or VKG is so low that workers need to perform excessive and health-damaging overtime to earn a living. Yet these facts don’t concern the apologists for GVC-led globalization.

In his best-selling Why Globalization Works, the Financial Times columnist Martin Wolf made light of claims that workers suffer in such factories:

It is right to say that transnational companies exploit their Chinese workers in the hope of making profits. It is equally right to say that Chinese workers are exploiting transnationals in the (almost universally fulfilled) hope of obtaining higher pay, better training and more opportunities.

In a similar way, former UN Millennium project director Jeffrey Sachs rejected accusations that sweatshops are exploitative. Rather, he argued that they were “the first rung on the ladder out of extreme poverty.” Sachs even claimed that “rich-world protesters” against neoliberal globalization “should support increased numbers of such jobs.”

In making such arguments, Sachs and Wolf hide behind the World Bank’s measure of extreme poverty — often described as the dollar-a-day poverty line. According to this measure, worldwide poverty has fallen significantly over the last four decades.

The problem with this measure is that it says next to nothing about poverty endured by real human beings. It is an arbitrary number, totally separate from any concern with poor people’s real needs. For example, in the mid-2000s, the World Bank’s poverty line was equivalent “to living in the USA with just $1.3 dollars to spend each day to meet all your survival needs.”The World Bank’s official poverty measure says next to nothing about poverty endured by real human beings.

This poverty measure does not identify the mechanisms that push workers into poverty. It assists pro-capitalist ideologues by conjuring up an image of a world where poverty is on the verge of disappearing due to the employment strategies of companies such as VKG, Foxconn, and Pegatron.

The poverty line that Sachs and Wolf use to justify and celebrate poverty-inducing work in GVCs is inhuman and anti-worker. If a worker consumes more than the equivalent of a dollar a day, but engages in health-damaging labor to do so — whether by working excessive hours or by laboring under dangerous conditions — the Bank counts them as not being poor. According to this measure, workers at VKG are not poor.

Putting Workers First

Rather than take such propaganda at face value, we can draw from the Marxist tradition to understand the prevalence of worker poverty under capitalism. Marx warned that capital “takes no account of the health and the length of life of the worker, unless society forces it to do so.” He also observed how capitalists would attempt, when possible, to bolster their competitiveness by depressing wages below the value of labor power.

The prevalence of worker poverty in GVCs suggests that they are not the generators of rising incomes, better jobs, and reduced poverty, as the World Bank and numerous academics would suggest. Rather, GVCs represent an organizational strategy for transnational firms, designed to raise exploitation by depressing wages below the value of labor power. While this strategy has done wonders for the profits of TNCs, it has subjected hundreds of millions to poverty pay and health-damaging work.

For Marx, poverty was a social phenomenon. In contrast with the World Bank’s inhuman poverty line, he explained how the definition and calculation of poverty was rooted in workers’ physical needs. Crucially, he noted that its measure included a “moral element.” This element is determined ultimately by the ability of workers to force capitalist classes to recognize them as human beings with a range of socially defined needs, rather than simply bearers of labor power — or animals, in the words of Foxconn’s Terry Gou.

Is it possible to imagine and bring about a world where poverty chains are a thing of the past? Part of this struggle is to recognize worker poverty where it exists, and to support workers campaigning and fighting against it. For these reasons, the lawsuit against Tesco deserves our full support.

There have been myriad struggles by workers in GVCs for better wages and conditions, from walking off the job in China’s giant electronics factories, to struggles for union recognition by Central American agricultural workers, or mass strikes in Thailand’s export garment factories. These struggles are the basis for a challenge to the power of TNCs and their global poverty chains.