Cuba and South Africa: Regionalism and Internationalism, Ideology and Conflict in Southern Africa during the Cold War.

Many historians have addressed East/West tensions and conflicts during the Cold War as contested spheres between the U.S and U.S.S.R. These tensions not only shaped diplomacy, technological expansion and weapons, but also challenged ideology in the form of proxy wars. In essence, the Cold War in historiography is consistently summarized as the United States vs. the Soviet Union. Conflicts outside this paradigm are marginalized. This is particularly true in the literature concerning the impact of the Cold War on Regional State actors and the international dimension of conflicts. Angola and Namibia are a case in point. The last major twentieth century Cold War clashes between sovereign nations were fought in Southern Africa. Despite the regionalization of the fighting, it became international when Cuban and South African Forces collided in these countries. Their engagement was unilateral and not as proxy states, although troops and arms came from a number of Western and non-Western countries. It was a unique confrontation between a Third World “Latin Power” and a highly industrialized African nation. Finally, the participants in these conflicts had diametrically opposing ideologies. South Africa, a regional African power was entrenched not only in an ideological struggle, but also in its physical survival, while Cuba’s engagement was termed “internationalism.” Was their engagement more than democracy vs. communism? What were the implications of their engagement?

Introduction

We frame the Cold War as the period between 1945 and 1989 when the Soviet Union and the United States faced each other in both conventional and nuclear showdowns. Both countries militaries were on heightened alert during the Berlin Crisis, the Cuban Missile Crisis, and multiple other near conflicts, which could have very easily resulted in nuclear war. Nevertheless, there were direct interventions by American troops in Korea and Vietnam, and Russian troops in Afghanistan. In these conflicts, both counties inserted troops to fight conventional and insurgent wars to preserve an ideological stance and hegemony. However, there was no large scale direct fighting between Soviet and American troops. Both countries fought each other through proxy wars during this intense period. No country was immune from Great Power politics or conflicts. It was a global war of contest spheres fought in Latin America, Asia, and Africa. Sovereignty was a moot point; both sides intervened in countries to booster their own interests, overthrowing governments and sending arms and military advisors to opposing militias; millions died. It was what Otto Von Bismarck called, “a test of blood and iron.”

Regional conflicts between countries, which had similar ideologies, and similar grand strategies were not considered significant at the time. The Great Powers simply saw themselves as the grand chess masters. Regional powers often pulled the United States and the Soviet Union into their own agenda. This was the case in Southern Africa.

South Africa and Regional Power

During the 1960s, a number of countries comprised the region known as South Africa. They included South Africa, West Africa, Mozambique, Angola, and Rhodesia; governed by white minority administrations, and Malawi, Botswana, Swaziland and Lesotho, ruled by indigenous African regimes. Economic and substantial trade between them connected each of these nations to one another. Goods and services were carried abroad from the interior to seaports in South Africa. “Long-standing labor migration patterns found over one million non-indigenous Africans working in Rhodesia and South Africa at any one time.”

South Africa needed this labor and Black Nations which had economic ties to South Africa were highly criticized for sending their citizens to work in South African quarries and agricultural works. Yet the reality for Nations maintaining contacts with the racially stratified State had to do more with real politics than idealism.

Botswana and Lesotho are land-locked and can only conduct trade by way of South Africa. Swaziland, close by the Portuguese port of Lourenco Marques, was in the same situation. All three, plus Malawi, had labor ties with South Africa. It was estimated that one-half of Lesotho’s adult males were working in South Africa at a given point; their transfer of funds back to Lesotho encompassed a significant fraction of Lesotho’s national income. To a lesser extent, the economies of Swaziland, Mozambique, Botswana, and Malawi were also dependent on remittances from their migrant laborers in South Africa.

South Africa also gave ample substance to conserve the enduring white-governed states of Rhodesia, Angola, and Mozambique, which surrounded her, through monetary and armed alliances. It was particularly anxious and hostile to African nationalism and at all cost wanted to prolong white rule in the Southern region. Thus, South Africa shaped a relationship of totality and hegemony. On its outer borders is the nation of Angola, one country above Namibia.

South Africa was interested in Angola because of its oil, diamonds, coffee plantations, and untapped mineral resources, as well as its fertile agricultural potential. Angola was one of the richest counties in the South African Regional partnership and was needed to maintain its hegemony. Angola, however, also had a very active insurgence movement, which challenged its continued dominance. Its closest neighbor, Namibia also had a guerilla organization, which fought periodic battles against the South African Defense Forces (SADF). The South West African People’s Organization (SWAPO) was bitterly opposed to colonialism and felt only a protracted Marxist war could liberate the country. Given SWAPO’s ideological beliefs, it was viewed as a direct threat to South Africa’s continued control. Politicians and military strategists in Petrolia felt a strong military response was necessary if it was to maintain its status of supremacy.

Communism and South Africa

The South African Nationalists assumed Communism would destroy their “way of life, unleash black opposition within its boarders, and create general mayhem.” They felt Communist forces wanted to have access to its deep-water ports and mineral riches. They reasoned that it was not domestic or external policies, which fostered discontent, but Communism. In essence, South Africa could not see it was fighting against a crest of Nationalism, but believed Marxism threatened its supremacy. Further, it reasoned that the front line of the Cold War against Soviet intervention was the Horn of Africa.

As President Mr. Vorster stated,

Russian and Cuban aims are not simply the establishment of a Marxist state in Angola, but to endeavor to secure a whole row of Marxist states from Angola to Dar-es-Salaam, and if it is at all possible to divide Africa into two in that way…A Marxist Angola does not simply mean the creation of a Communist state in the heart of Africa, with all the potential this offers for Communist mischief in regard to neighboring states such as Zaire, Zambia and others, but it undoubtedly enables the Communists to stand astride the Cape seas route and to act at will as they find it necessary to determine of the Free World and the West…If Africa and the Free World allow one African country…to be hounded into the Communist fold at the point of bayonet, Africa will pay the price of enslavement far worse than the of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

Cuba and Internationalism

The national hero of Cuba’s fight for independence Jose Martí viewed Cuba’s struggle as one that would liberate the Americas. He was not simple fighting to end the long years of Spanish dominance, but “was also fighting as an international revolutionary to secure the liberation of his continent, and indeed of the world” The hundreds of Cubans who volunteered to resist fascism for the duration of the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939) reflected internationalist perception. Jorge Risquet, an important spokesperson in Cuba’s internationalist operations, argued, “in proportion to its population at the time, Cuba was the country that sent the most volunteers to Spain”.

The Cuban revolution endorsed the concept of internationalism and made it an unequivocal component of the State’s role in world politics. Jose Canton Navarro noted that the consciousness of the people of Cuba in their long fight for independence was attained and expressed in revolution. The move away from a semi colonial state to find its path towards a nation filled with revolutionary spirit was Cuba’s destiny. Thus, the new Cuban government understood it had fulfilled a long historical journey that was at the core of its existence: internationalism.

However, the revolution’s explicit goals centered on building a society rich in socialist thought that could defend it from a powerful peripheral adversary. This outside force, the United States, gave new direction to Cuba’s intercontinental perspective and coupled it with the survival of their revolution. Capitalism and Communism were in opposition to one another and could not exist in the same sphere according to Marxist/Leninist theory, hence a U.S and Cuban standoff.

Revolutionary self-dense, as Castro stated, was internationalism. It served to offset aggression against Havana, set in place by successive American administrations, which attempted to isolate the island nation. Speaking at the Second Afro-Asian Economic Solidarity Seminar in Algeria, Che Guevara emphasized the magnitude of Cuba’s obligation to internationalize the Cuban experience elsewhere in the world.

Che’s stance on the role of their revolution was articulated in the First and Second Declaration of Havana. The amendments were approved between September 1960 and February 1962. These documents rebelled against American expansionism and coupled Cuba’s Revolution with the fate of Latin America. Further, it was a call to arms and a declaration of independence, stating liberation from imperialism could only be achieved through revolution.

Che’s philosophy was correlated not only with Latin America but also with armed resistance wherever colonialism existed.

Internationalism was further associated with the liberation of people living under racial oppression. This principle buttressed by the revolutionary leadership in Cuba called for the eradication of racism. The central core of this thesis can be found in Cuba’s history of slavery. Thus, Cuba’s intervention in Africa liberation struggles was justified as defending the continent and repaying a historical debt owed by the descendents of a former slave population.

When Cuba intervened in Angola, the operation was named after an African slave woman who led a rebellion in early Cuban history. The military incursion, operation CARLOTA was commenced on the anniversary of Cuba’s triumph at the Bay of Pigs. During a speech, which addressed why his troops were taking on a combat role in Africa, Castro stated, “Cubans are a Latin-African people” and that it was their role to protect her.

Changes in Hegemony in the Southern Alliances and Cuba

As changes took place across Africa and one nation after another became independent, South Africa found itself isolated and surround by hostile states and a growing insurgence within its own country. It was fighting multiple conflicts, which sapped it of manpower, resources, and money. South Africa’s military raids into neighboring countries was known as the “Border Wars.” Its internal opponent was the ANC and its external enemies, Marxist guerrilla movements in nearby states, and Cuban/Soviet intervention.

Liberation Movements and South African Hegemony.

The Border War raging across Southern Africa also included the nation of Mozambique. This war was cross borders and Mozambique was within easy sticking distance of the South African Military. It was in coordination with both Rhodesian and Portuguese armed forces. When the settler population left, the country moved towards independence and South Africa were forced to defend itself. During the liberation struggle, Chinese and Cuban Advisors instructed not only the insurgents in that country, but those who were waging armed struggle within South Africa itself. Thus, Mozambique was a prime target for covert operations.

After Mozambique became independent, the leading liberation organization in that country (Frelimo) allowed the African National Congress (ANC) to maintain guerilla-training camps within its borders along with Cuban advisors, until the signing of the Nkomati Accords with South Africa. Under these Accords, Frelimo would close ANC bases of operation. The Accords created further strategic problems for Cuba, the ANC, and other guerilla groups, which had based their strategic and tactical operations there. The Accords also allowed South Africa a secure three thousand-mile boarder with Mozambique. Without question, this was a blow to Cuban internationalism, which had sought to roll back the South African Military and challenge China’s influence.

Frelimo felt no kinship with Cuba; instead, it sought armed support from the Chinese government. During the Rhodesian uprising, Mozambique allowed its seven hundred-mile western border to be used by Zimbabwe African National Union (Z.A.N.O), headed by Robert Mugabe in the event the Rhodesian and South African governments fostered either a successful counterattack or counterrevolution movement in Mozambique.

However, by 1978, after independence and a change in military alliances, Frelimo allowed over a thousand Mozambican secondary students to study in Cuba. According to a highly respected source it was noted, “more than six thousand five hundred Mozambican were studying in Cuba” by the 1980s. Cuban influence had not replaced China’s, but a convincing argument had been made that educated students would make a difference in a war torn country attempting to govern itself.

Further, thousands of technically instructed professionals were returning home, having been educated in the Cuban educational system. Cuban teachers had made a difference in Ethiopia and other counties and this fact had swayed the most diehard, that although they may not like Cuba’s form of Marxism, they needed trained technicians to run their nation. Revolutionary internationalism also encompassed education and successfully trained a generation of professionals.

Changing Tides

Further change followed when a group of young Portuguese officers exhausted by unending wars in their colonies overthrew the dictatorship, of Marcello Cuetano in Portugal. Not long afterwards, negotiations called for decolonization of all former Portuguese colonies. Now it was Angola’s turn to taste freedom. An accord was quickly fashioned to construct a political agreement between three groups posed to lead the newly independent country. The innovative new Portuguese government soon accepted the fact that no one liberation organization was in place to govern. Hence, the “Alvor Agreement” attended by the MPLA, FNLA, and UNITE was convened. These power-sharing groups had long battled the Portuguese military and continued to be quite antagonistic towards each other. Although they agreed to work jointly with the Portuguese until sovereignty, within a short period this pact unraveled and full-scale civil war commenced.

The most essential of the three groups was the MPLA. The South Africa military or South African Defense Forces (SADF) was anxious to destroy it. Military leaders feared it posed a significant security threat to its occupation of Namibia (formally Southwest Africa) and to long-term white minority rule. In concert with the U.S. backed FNLN and UNITA, South Africa Defense Forces invaded Angola in late 1975.

From Cuba’s analysis, Angola was significant to South Africans continued supremacy of Africa; as a result, Castro commenced military operations to help the MPLA stop the South African incursion. When Castro spoke before the Cuban Communist Party’s First Party Congress in December 1975, he declared the rationale for Cuba’s intervention. Cuban troops were sent he said, because South Africa’s occupation of Angola poses a threat to the whole of Africa. This occupation of Angola by the South African racists poses a grave threat to Zambia, to Mozambique, to Zaire, to the People’s Republic of the Congo and to the whole of Africa and in this struggle; the Cuban people will be on the side of the African peoples!

The conflict included,The smallest guerrilla body, the MPLA was the only Marxist-oriented movement. Its main ethnic support came from the Kimbundu. Located in the countries west-central provinces, they were the most urbanized and wielded a disproportionate amount of influence in the capital, Luanda.

The U.S entered Angola alongside South Africa commencing covert operations. Nineteen seventy-five had been a particular bad year for the U.S., Saigon had fallen to North Vietnamese forces and America needed a military victory. Henry Kissinger was not about to allow another communist take over on his watch.

In the early fall of 1975, the MPLA was simultaneously attacked by Zairian and FNLA units. It was now prudent for South African Defense Forces to take the initiative. This had the potential of allowing SWAPO to operate campaigns against South African’s interest in Namibia. Outnumbered and faced with multiple opponents who were attempting to encircle them, the MPLA appealed for Cuban troops. Discussing Cuba’s military intervention, Castro simply affirmed that Cuba had no stake in the ongoing war in southern Africa, in his own words “We do not need anything in Angola,” Cuba, he said, was simply pursuing its “traditional policy of internationalism.” According to Piero Gleijeseses, the Cubans asserted that they did not inform the Soviets until after the decision had been made. Castro said that was Cuba’s decision.

Soon, the Soviet Union gave Cuba its most sophisticated weapons to fight the SADF, sending ships filled with Soviet advisors, tanks, aircraft, artillery, and armored personnel carriers. It was not a battle it wanted nor asked for, but in order to save face, gave Cuba what it needed. In essence, Castro’s independent foreign policy pulled Russia into a conflict in which it otherwise would not have directly become involved.

American diplomatic and military leaders felt the specter of Vietnam might be banished by a demonstration of American power in the Region. In the wake of our humiliating retreat from Cambodia and Vietnam, allies around the World began to question U.S. resolve. “Against this backdrop, Angola commenced to attain a particular significance. It presented both a chance of redemption and a threat of failure: America’s resolve would be tested.”

The Soviets responded to contest spheres of influence in Africa between themselves and China. The Soviet government was not about to allow this rivalry to go unchallenged, their prestige was on the line, and they could not allow the Cubans not to have advance weapons systems at their disposal. A Cuban defeat was paramount to a Soviet defeat in Africa. Further, Castro understood its long history of slavery, which struck a historical cord with Cubans of Angolan descent. Many of his soldiers were the descendents of slaves and felt they were giving back to Africa that which had been taken from their ancestors, freedom, a key element of internationalism. Fierce fighting ensued, but after the defeat of the South African alliance in Angola, many Cuban military personnel remained to help develop its infrastructure and ward off counter attacks by the SADF. At the height of their deployment, Cuba had thirty six thousand troops in Angola. To their tribute, the Angolan forces were able to sustain their position of power not only because of Cuban troops, but also as a result of having built solid coalitions over the years with guerilla units in Namibia and Southern Africa. This allowed the MPLA to receive vital intelligence about SADF’s military movements, which gave them time to build up their forces and prepare for contingences. Since the South African Military was on the Namibian border close to Angola this information was vital. It was only a matter of time before they launched another attack.

In addition to providing military aid, Cuba assisted Angola by providing educational, medical, and economic aid. At the time of independence, over 90% of the Angolan population could not read or write. In June 1977, an educational program was in progress and over two thousand students were given scholarships to attend Cuban schools. According to one account, nearly a thousand Cuban volunteers went to Angola to work as primary-school teachers.

In December 1977, addressing the first Congress of the MPLA stated that when the Portuguese left the country there was only one doctor per one hundred thousand inhabitants; now there were ample physicians. Medical groups were operating clinics in isolated sections of the country as well as hospitals. By the end of 1982, over ten thousand Cuban construction workers had seen service in Angola.

Second invasion: the Siege of Cuto Cuanvale

With the incursion of the Cubans, President Ronald Reagan altered U.S. foreign policy towards Angola. He wanted to foster better relations between America and South Africa. This change was in line with his overall view that “regional conflicts in the Third World should be seen as an overall competition for influence between America and the Soviet Union.” Although the U.S had made every effort to stay out of the political and ethical issues connected with South Africa the need to be seen as a powerful country opposing Communism was necessary. Reagan was following the Truman Doctrine, stopping Communism wherever it was a threat and his own realist policy to confront Russia.

By December 1987, the United States openly supported both UNITA and SADF and supplied them with surface-to-air Singer missiles and BGM-71 TOW anti-tank-missiles. The U.S. Congress rescinded the Clark Amendment giving millions of dollars in overt military support to UNIT. Meanwhile, the Soviets upgraded the MPLA’s equipment with 150 T-55 and T-62 tanks as well as Mi-24 helicopters.

As the fighting intensified, South African and UNIT troops were committed to take a vital Angolan airfield in a small town known as Cuito Canavale. South African Forces bombarded the town, rendering its airfield and many defensive works useless. The settlement occupied by both Cuban and MPLA troops came close to falling, but held out. A costly deadlock insured. “The battle for Cuite Cuarnavale was one of the largest engagements of its kind ever fought on the African continent, exceed in size and intensity only by the North African campaigns of World War II.”

Conflict Resolution in Angola

In April of the same year, fifty thousand Cuban troops were added to the front lines moving towards the Namibian border. They brought with them tanks and armored personnel carriers. Within a short period, the Cuban Air Force gained strategic dominance, thus denying SAFD troops air cover. If South Africa were to continue its assaults, it would take high casualties. This forced a termination of hostilities, a cease-fire, disengagement, and effectively bought all parties to the negotiation table.

The success at Cito Cuanavale allowed Cuban and Angolan forces to negotiate a series of constructive treaties, which lead directly to the liberation of Namibia. Within a short period, the combatants entered into further negotiations. Cuba promised to withdraw its combat troops from Angola in return for a South African army extraction from both Angola and Namibia. Additional discussions, called for elections in Namibia with SWAPO’s involvement. Finally, all parties agreed to this binding arbitration.

Conclusion:

Despite its size, Cuba has played a major role in the liberation of many African Nations. Its concept of revolution and particularly the humanitarian aspect of that ideology have allowed it to walk on the global stage and been positively received by some while being condemned by others. Yet there is no denying that the key component of internationalism was conceived in its revolts against oppression. The idea that the liberation of Cuba was just one-step towards the liberation of the Americas was essential. It was also this hallmark, the emancipation of people, which made it distinct from other revolts.

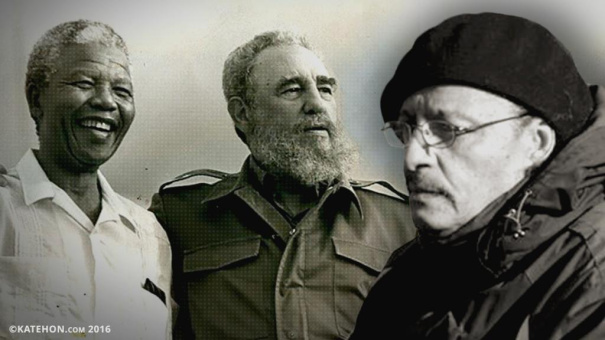

It is this history, conceived by the oppressed, which allowed it to blossom into an ideology, which challenged and galvanized its people to see themselves as internationalists. The nature of this idea did not allow nor settle for Regionalism. In fact, Jose Marti, Che Guevara, and Fidel Castro pushed the motivation and cultivation of this idea. It also had its roots in slavery. Foreign policy built on this philosophy has a different perception of its place in the global community. It views itself as liberator. Of course, it is up for debate whether it is or not. However, when seen from this view it was not difficult to imagine how Cuba was able to link itself to anti-colonial movements.

South Africa was also born in struggle; the Boer Wars enlisted a long guerilla war against the British. Although its outcome was different from Cuba’s, the State viewed itself as one, surrounded by hostile tribal States; it had to defend itself. Thus, the more territory it accumulated the safer its inhabitants felt. The need to Regionalize was an outgrowth for its need to protect itself and to insure that those who came into collaboration with it served as buffer zones; thus protecting the State and State interest. This was a reciprocal relationship based on real politics.

South Africa often called itself democratic, and yet democracy was only for a few. Cuba called itself Socialist, which made the two states incompatible. Cuba’s socialism never totally developed, due in part to constant U.S. intervention, but it could be seen in the various countries where it sent doctors, teachers, and construction workers.

Cuba was not a proxy for the Soviets, they did not tell the Russians of their intention to send combat troops in either the first or second Angolan wars, and in fact placed Russia in a difficult position, it had to support Cuba’s efforts. This is also true with South Africa; despite its dismal racial policies the U.S was encouraged to become part of its Regional plans once it was stated Communism was at the gates of the Horn of Africa. In addition, U.S. pride was at stake. After the Vietnam conflict, it needed a victory.

This paper shows the development of different ideologies and how they were used to justify foreign policy. Further, how two divergent countries intersected and clashed in Africa, as each sided with various guerrilla organizations seeking supremacy, and finally how it was possible for Regional powers to manipulate Great Powers into their political agendas.

![Thomas Nast [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://katehon.com/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail__270x150/public/1024px-cincinnati_convention_of_liberal_republicans.png?itok=OzNA8waa)